Share Post

I learned to drive on those East Texas red clay backroads,

and I mean to tell you my friends, they weren’t no easy roads…Michelle Shocked, Memories of East Texas

– I –

Last summer we put

a chicken carcass out

in the rubbish, in the heat.

By week’s end the whole bin

was infested with maggots,

squeezing and squirming,

turning and turning.

My stomach turned too,

and I sought shelter in Jeyes fluid,

liberally applied. Undaunted,

the maggots continued

their grim dance of death.

I shut the bin, tight,

and put it out in the road:

out of sight, out of mind.

But a place inside me,

tight shut for thirty years—

out of Africa: out of mind—

came open; came apart.

Early mornings reeking

with Jeyes’ sharp tang,

late evenings with the sickly

sweet breath of blood and alcohol.

Midday sun on blowsy bougainvillea,

drowsily digesting doughnuts and fanta;

mid-night glint from bared metal bedsteads

dully reflecting a single, stuttering strip.

Surgical gloves, boiled and reboiled, falling apart.

Green needles, reboiled and reboiled, entirely blunt,

eliciting groans from comatose patients,

tearing the flesh as they plunged into muscle.

And the taste of hot chai,

brewed straight from the instrument boiler.

The lone, lonely doctor, polio lame,

his sterile, gloved hand supporting his knee

as he hobbled to the patient.

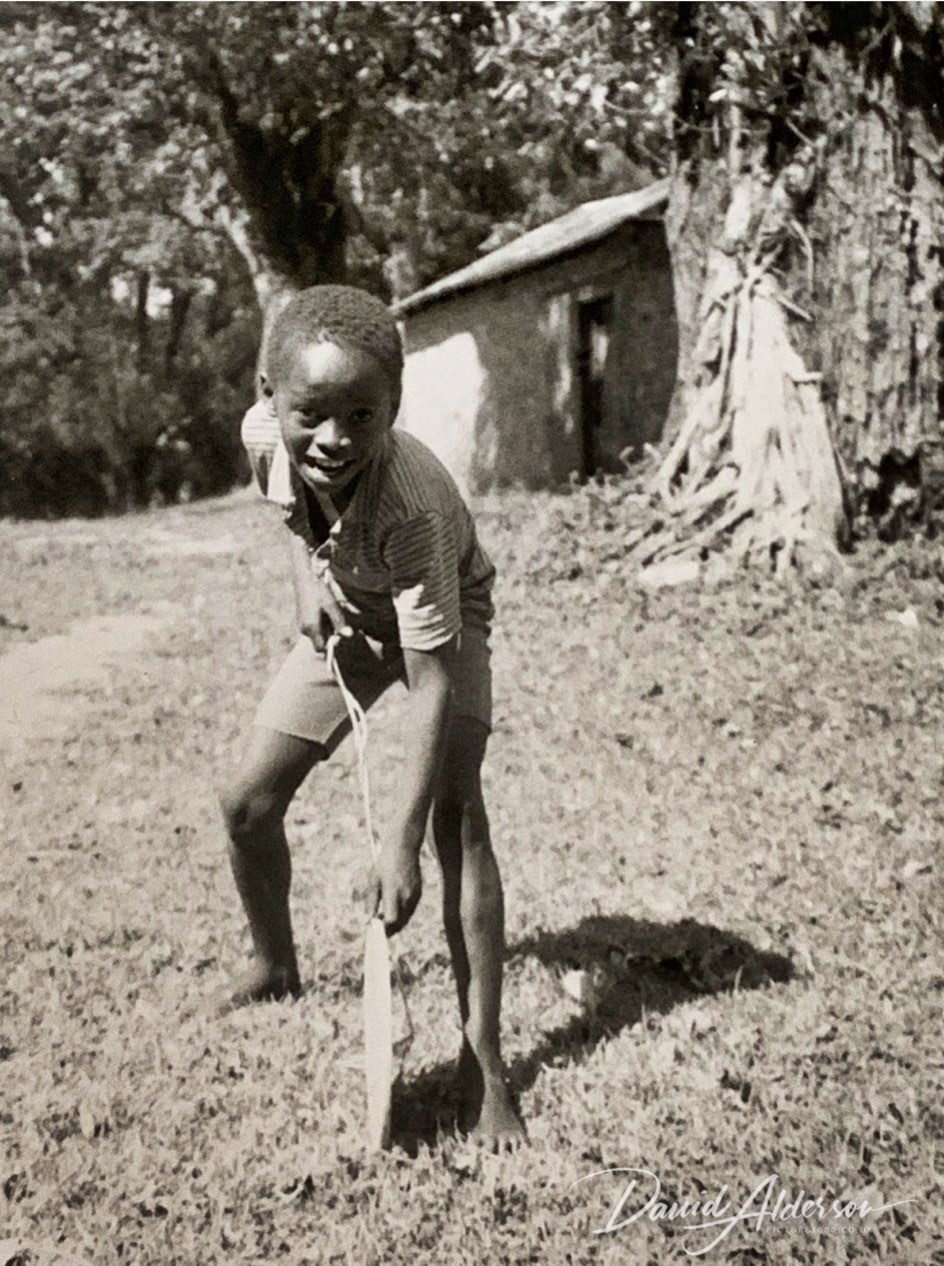

And the little boy who befriended me,

shouting mzungu with joy.

Whose picture I took.

Whose picture I have.

Whose picture I promised to send.

And so easily could.

And never would.

Memories of East Texas

playing in my head;

memories of East Africa

replaying and replaying in my mind.

– II –

My first night on call,

my first patient:

with seventy percent burns.

She had confronted her husband

about his girlfriend,

and he had responded in kind,

with kerosene.

The doctor sited her drip:

fluids, fluids, if nothing else,

I knew she needed fluids.

Three a.m.,

a soft tapping on my window:

a tissued drip and the nurses

had tried for two hours.

Cold and clammy,

and smelling of death.

I struggled for a vein,

then: “Call the doctor.”

And again, then again:

“Get the doctor.”

Desperate now:

“Call the doctor.”

I found him in his room, asleep.

“I thought it was just the nurses. I’ll come.”

How callous to sleep

while his patient was dying.

But she was unconscious,

his on call relentless,

and she could never survive.

– III –

A panga slash through

a teenager’s brow:

an everyday trauma

I knew how to treat.

I sutured it – beautifully

knots tensioned, evenly

skin aligned – flawlessly

Next day he was swollen

like an overripe fruit,

both eyes squeezed shut

by the tension inside.

We cut out the stitches

and pushed out the pus.

Washing and washing,

rewashing the wound.

All that night

I pictured him

turning the corner

but he turned another

o p i s t h o t o n u s

a lumpen word

for the living hell

of lock-jaw.

There’s a picture by Bell, from 1809,

that shows such a patient,

contorted in truly, terrible agony.

It doesn’t come close:

back arched

beyond breaking

face a grim mask

teeth cracking

bones snapping

as the axial

spasm increased

and increased

and increased.

There was little we could do.

I looked in a book

and rushed to tell

the doctor that

we could give

more diazepam

He and the nurse

exchanged a look

but he gave the dose.

Soon, the spasms relented.

As did his breathing.

As did his life.

Cold comfort from the

doctrine of double effect,

but I was glad that

his suffering had ended.

Though mine had not.

– IV –

The fretful, young mother

waiting, on New Year’s Eve.

Her baby, wrapped tight,

showing only her face,

serenely asleep.

I smiled reassurance

and human connection,

then waited in silence

for a nurse to interpret

her Kiswahili.

But suddenly panic:

a torrent of trauma

flowed from the road.

Man v matatu

on the crest of the hill.

Fleeing the mob,

the driver had sealed

his passengers’ fate,

when he failed to engage

the minibus brake.

Then wave upon wave

of changaa fuelled violence

broke over us, swamped us,

and finally snuffed out

the remains of the day.

The newborn new year

found me first footing,

a faltering flash-light

showing the way

to the unlit, unlovely

hushed, mortuary hut.

On the cold, metal table,

carefully wrapped,

a small parcel:

the babe

from the year

and the lifetime before.

If all this were fiction,

the telling detail

would be considered grotesque,

gratuitously graphic.

But this being real,

it emerged nonetheless:

Lifting the flap

of her rent apart scalp,

torchlight probing for

the fatal fracture beneath,

a monstrous ant scuttled

from the depths of the wound

onto and over her still serene face.

– V –

Years later,

a nurse queried,

where was my humanity?

What answer could I offer?

Lost, in Africa?

Hiding, until

it was safe to come out?

I returned intact,

no HIV, typhoid or bodily trauma.

But unscathed?

I think, perhaps not.

Comments are closed.