Share Post

How do we help students develop the real world insight and judgement so vital for clinical practice? What is the role of the teacher in reflective practice?

Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge?

Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?TS Eliot, The Rock, I

In Treatment of Failure, I share an experience I had as a first year medic, shortly after arrival in a small hospital in the Highlands of Scotland:

All this last week, I’ve charted your course,

as you tacked back away from these perilous shores,

and chest-sounded, deaf to your treasures and fears;

but now, you are fighting each shuddering breath,

with unseeing eyes and fast failing strength,

yielding the helm to those base mutineers.

The patient was recovering from a heart attack, but had developed heart failure. Not an unusual situation. Something I had been trained to assess and manage:

that quantum of knowledge marked, Treatment of Failure,

drug, route and dosage, all faithfully scribed.

As I squeezed a diuretic into her drip, she started to rally; soon her breathing eased and she was able to hazard a smile. I was used to checking management plans with the nursing team, but the nurse-doctor relationship here was very different from that which I’d previously experienced:

“What else should we do?”

“You’re the Doctor,” she says pointedly, “you tell me.”

So, I sought certainty in a well thumbed textbook: what else should I look for? Within minutes my bleep went. The scene had changed, dramatically, for the worse; even as I watched she lapsed into unconsciousness.

In that moment, five years of training at an elite medical school and six months of practice in a London teaching hospital counted for nothing. With no-one else close enough to call—I was the only resident doctor—my brain simply froze in kernel panic:

The Kingdom of Knowledge is engulfed by the sea.

And I helplessly watch, as you sink without trace.

As her breathing failed, I asked the night nurse if there was anything she thought we should do. “We could get the crash trolley, I suppose—”, “Yes, get the crash trolley!” “—but I don’t think so.” Already, the patient had given up her struggle.

I sat in the doctors room, head in hands, trying to make some sort of sense of what had just happened, trying to hold it together:

Knowing I’ve failed you, I’ve no way to constrain

the anguish and grief of a desolate ocean.

The door opened and, without warning, the nurse showed in the patient’s daughter: “The doctor will explain.” All I could muster was: “I’m afraid your mother’s just died.” It wasn’t enough; and it compounded my feelings of failure.

My problem was not lack of knowledge. Intensive training meant that I knew about heart failure and cardiac arrest; I could quote verbatim the schedule of drugs and electricity needed in different rhythms, and had participated in numerous arrest calls. But this information, these packets of knowledge, existed in quite separate parts of my brain. There were no connections between them and they had little meaning in a complex, rapidly changing scenario—where a patient transitioned from talking to unconscious to dead within a few short minutes. I knew about breaking bad news and knew that sometimes doctors made mistakes. But again this knowledge found little application in the predicament in which I found myself.

Competent practitioners usually know more than they can say. They exhibit a kind of knowing-in-practice, most of which is tacit.

Donald Schön

Donald Schön writes about the difference between technical-rational knowledge—knowing about, or knowing that—and professional-artistry, the practical know-how of getting things done. Technical-rational knowledge is explicit—it can be analysed, written down in books, tested with exams—and occupies the academic high ground, privileged by university courses, professional bodies and regulators. Professional-artistry, meanwhile, is concerned with the swampy lowlands, with reality on the ground, with practical wisdom. It is implicit—difficult to define or analyse—but fundamental to every area of practice.

Knowledge and wisdom, far from being one, have oftimes no connexion.

William Osler

In Hard Times, I discuss a Transmission Perspective on medical education—knowledge transmitted directly from the trainer’s sphere of knowing to that of the trainee. The formal curriculum of my undergraduate course was largely based on this model: it fits well with a technical-rational view of what a doctor needs to know. But it fails, disastrously, when faced with the uncertainties and challenges of real practice.

What we call sense or wisdom is knowledge ready for use, made effective, and bears the same relation to knowledge itself that bread does to wheat.

William Osler

How then can we develop the practical wisdom that we need alongside academic knowledge? Schön proposes the reflective practicum, a safe approximation of the real world, that can be jointly explored by a student and a guide: a virtual recreation that refines and condenses the complexities of practice, while remaining true to that world. Bente Elkjaer writes about the way that this practicum can develop creative and critical thinking: drawing on imagination and reflection; forming meaning and sense from what has happened, but particularly focusing on future practice; exploring the question – what if?

The ability to recognise liminal zones is crucial…timely and effective action can halt progression towards danger…Inaction, by contrast, may lead to exacerbation of risk and spiralling danger.

Roger Kneebone

The reflective practicum has been widely adopted within medical education and takes many forms. Scenario-based simulation can help to make links between, and give context to, discretely stored packets of academic knowledge. Roger Kneebone writes, for example, about simulation helping us to recognise and navigate the liminal zones, as a patient transitions from stable to mild heart failure, to crashing failure, to cardiac arrest.

The creative arts can help us to recover a sense of our shared humanity: the person in the patient, and the human in the healthcare hierarchy.

David Alderson

Sharing stories about the impact of practice on our inner lives, in a Schwartz Round perhaps, can help us to support each other in the emotional challenges we all face, easing the feelings of isolation which attend the inevitable difficulties and failures of that practice. It can help us to empathise, understanding how the world looks through the eyes of the people with whom we work, and for whom we work. Small groups can use both personal experiences and the vicarious experiences of the arts and humanities to explore these areas further, considering for example what breaking bad news might look like if you yourself are already drowning in a bitter ocean of grief, guilt and shame.

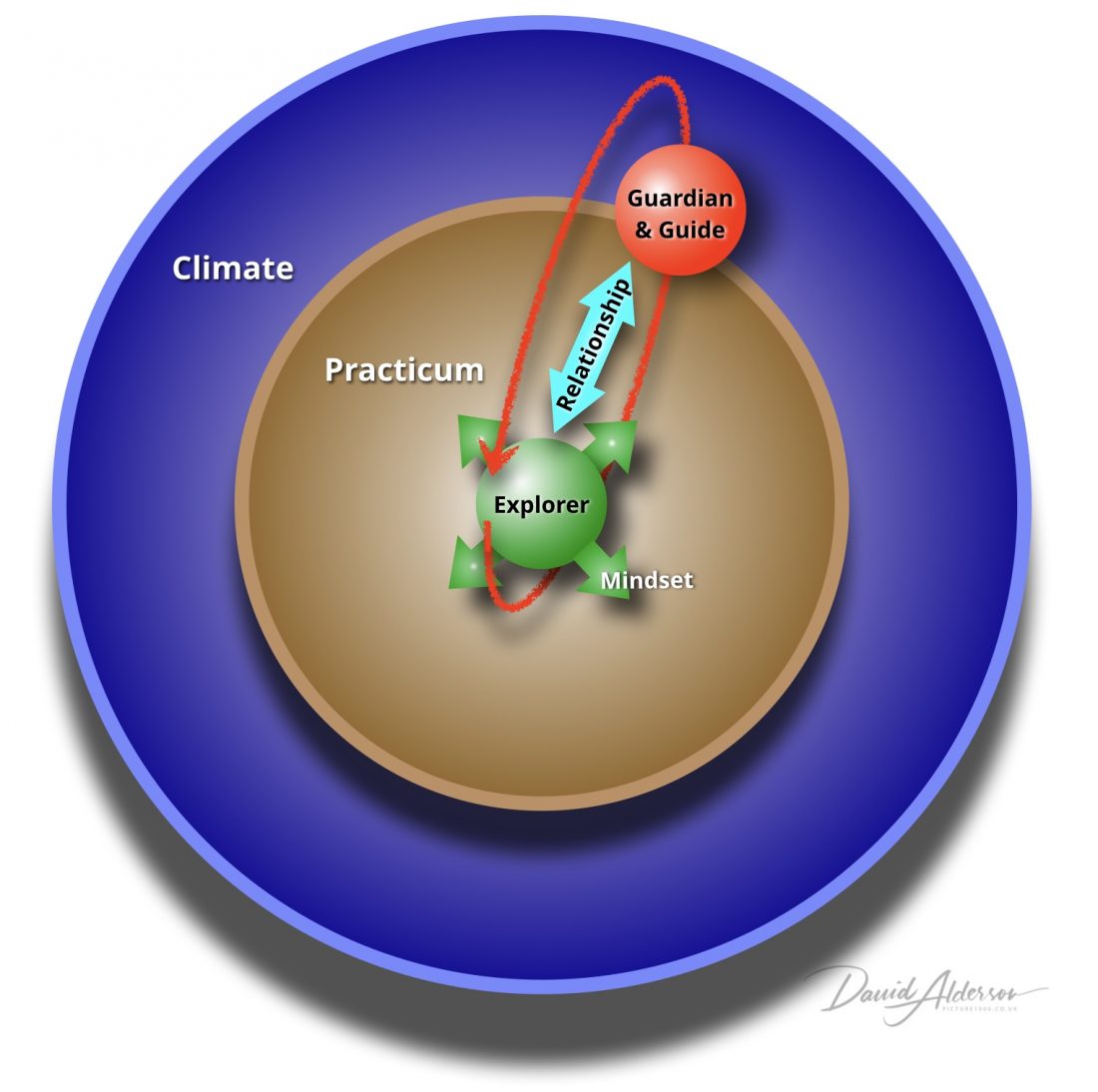

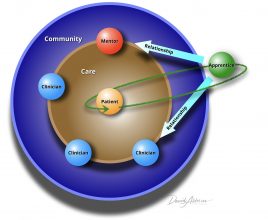

These examples of a reflective practicum, however, represent a challenging environment for a teacher grounded in a Transmission Perspective. The picture illustrates some of these challenges, drawing on Daniel Pratt’s concept of a Nurturing Perspective.

The teacher’s role is that of facilitator: morphing between guardian of, and guide to, the practicum. First, as guardian, they must first look from the outside: setting up a climate conducive to exploration, considering confidentiality, mutual support and the avoidance of judgement; defining the boundaries and nature of the practicum; encouraging a growth mindset; building the relationships—with, and between, each student—that become the fundamental pre-requisites of learning.

They must then join their students inside the practicum, in joint exploration and reciprocal learning, guiding an expectation of fruitful engagement—not only in their students but within themselves, aspiring to learn as much from each interaction as their students. They may draw on their experience of clinical medicine, but they do not claim to have answers ready to pass on: the spheres of knowing are now of an equal size.

Unless they can achieve this paradigm shift—away from trying to impart their own knowledge and expertise—the practicum remains a hollow shell, the simulation a dangerous sham, the small group sterile. With a successful shift to a Nurturing Perspective, however, the practicum fills with rich, fertile loam, and practical wisdom can begin to grow.

Knowledge, a rude unprofitable mass,

The mere material with which Wisdom builds,

Till smooth’d and squar’d, and fitted to its place,

Does but encumber what it means to enrich.

Knowledge is proud that he has learn’d so much,

Wisdom is humble that he knows no more.William Cowper, The Task

Read more of my thoughts on reflective practice here